Photo by Chris Reed

Category Archives: Personal Practice

Chris Reed’s personal art as research practice.

This is informed by 40+ years work in caregiving, experiential and outdoor learning, the arts therapies, particularly dramatherapy and 10 years personal art as research practice with a focus on health and wellbeing.

Sentences, Sensations and Subjectivity.

At the time of writing this post I am about 2 months into researching recursion through reading stuff and making stuff. It has been very fruitful. Doing and describing doing are still at war, but the further I go down the line of enquiry the less I trust words. The more I believe they are a trap. Words work for persuasion not description. I feel like I need to take heed of the title of the 1993 album by The Fall ‘Perverted by Language’. I feel like to be accurate, my research output should always teeter on the edge between the divine and disaster and be like this…

Part of this realisation came out of a podcast I listened to. The poem below, short but sweet, came out of the podcast I listened to. Here. The poem about the podcast goes thus…

Nominalism

I am disappointed to find there is

A name for what I believe

In the podcast Jody Azzouni, poet, writer, philosopher and Professor of Philosophy at Tufts University NY talks about nominalism, a form of philosophy proposing that words and numbers are made up things pointing to some real thing. Words and numbers are real in name only, they are titular and nominal. Before the podcast, I did not know there was a name for this, but on listening to Jody I was struck that this is what I believe. I found it hilarious that there was a name for the thing that said that the things in the world have no names. My belief system boiled down to one word. I felt at once ruined and relieved!

In nominalism, words and numbers are post res to reality, like a map is to a territory or a signpost to a destination. They are like what Fedinand de Saussare called the ‘signifier’ to the underlying thing, the ‘signified’ except Saussare meant they were both internally constructed, until Louis Hjelmslev moved the signified to become some objective thing, which is where it has stayed since. This makes nominalism interesting to me. To see the real thing it may be useful to forget its name. This changes the thing because it changes how you perceive its reality. Claude Monet, the painter said “To see you must forget the name of the things we are looking at.” It is in this sense that I encounter nominalism as a guide for art as research. I ask what would happen to this thing if I encountered it as if it had forgotten its name? What then would it have to say? I would have to say some new thing about itself.

To see you must the forget name of the things we are looking at.

Claude Monet

In reality, we could even be seen to construct even the object. I listened to this podcast here. In it Ed Yong talks about how animals and humans construct their world. In constructing our world, various philosophical ideas talk about sense data, qualia, and consciousness as hallucinations, but Yong talked about ‘Umwelt’. Translated from German it means ‘environment’ or ‘my world’ and describes how an animal constructs their perceived world from the senses regards the world it inhabits. So how we sense determines what we perceive. My local woods experienced by me would be different to the woods experienced by a mole or vole, or crow or crayfish. This fits with ideas about art making as an embodied experience rooted in the senses. It would fit with what Monet says. It would fit with what I experience through the intelligence of the materials I use in art making. I experience them sensationally and this crosses over to me becoming more attuned to experiencing the world directly through the sensations of art making. They are inseparable. I have a favourite quote from the progenitor of quantum mechanics Werner Heisenberg, who says “We have to remember that what we observe is not nature itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning” My contention is that with art making as a method of questioning, our mode of research physically changes the world we encounter. We make some new thing come into existence. Our personal subjective experience is central. This renders art as research unavailable for quantitative research. Art is performative and subjective research. But it introduces art as an adjunctive companion science. We can make a subjective form of an objective process, the subjective object, the art we make.

We have to remember that what we observe is not nature itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning”

Werner Heisenberg

So in making some new thing come into existence from our thoughts, our ideas, and our sensational encounters with the world, we make new things. We perform an act of poiesis. This produces a subjective object, an oxymoronic thing of magic realism. We make our research finding personal. This reminds me of the breathtaking opening paragraph of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ about the wonder of the world. Marquez writes ‘ Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so new that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point’. Marquez is saying things you make don’t need names. They exist without them. If we have experience and make it as art, words become secondary. The thing we make can speak for itself without words. This is the essence of art as research. We can show what we found through a physical act, we always don’t need words.

The world was so new that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.

Gabriel Garcia Marques

This page is an attempt to describe the direction taken by my work generally and by the exploration of recursion that follows. What follows is a summary of this direction as a poem. The poem goes thus…

Work Here

My work here

Is undertaken on an assumption

That we can be

Sceptical about sentences

But

Not about sensation

And

The reality we research

Is the one

We create for ourselves

A still moving subject

Always out of reach.

Indian Ink & Acrylic

Artwork by Chris Reed

Three Cursing Crows

Croci the Crow cronked a cronk. A cronk is a crow call that says ‘ There is that man from the car there, with a clipboard, a pencil, three cages and his bag of carrion’. The man just heard a croak and a collective set of caws returning the call around him in the woods. ‘Well,’ the man said ‘the crows are definitely here.’ and put down his bag of carrion, the caronia carcass. The prize. Croci had smelt it before the man entered the woods. Before he got out of his car. Croci had called the call ‘cawcsss’ (with silent sss, at least to men) and as one, the crows converged, convened and conspired to steal his food.

One crow is all crows. They live en masse. No crow ever leaves the side of another crow. See one crow and you know some other crow is nearby. Each crow lives bracketed, like a word in sentence speaking about crows and what they intend to do. Crows calling to themselves be outspoken and literate in the wild non-human world, in the city, in the sky, on the rubbish dump, over the mountain top. Everywhere. Crows calling together to echolocate their fellow crows, and hear their own call answering back, in the throat of another crow. And these crows spoke of theft and trickery, because tricksters were them all. The thing with the crow is they go with the flow, because adventurers were them all. Whatever the outcome, in the end they would return, trick away and escape and curse and re-curse the fools who tried to trick them one and all.

Croci set off the moment the bag of sweet smelling rotten flesh hit the floor. All the crows so, set off too. All crows landed so, in a circle around the man and his soon to be stolen bag of booty. Croci hopped right up to the man and his bag. Two crows followed and triangulated him, took their third of the prize, and hopped into the cages to eat alone together in peace. They even closed the cage door, with click and clack and a corvidian caw. The caw is the call that says ‘We have him. He is ours’. It is said of men. Which is why man only notices this call. It’s subtext is ‘Sucker! and if crows could grin it would be said with a grin. The man was pleased. He had to get three crows for an experiment and had planned for it to take a month or more to train the crows with food, to trick them into the cages and carry them off to his lab and test them. But the trap closed on him the moment he carried the three crows to his car in cages, and put them in.

The car was warm and with their bellies full the crows slept. They woke at the lab as the cold air tickled their nostrils and were put in a cage indoors together on one perch, together as a three. The man went home, pleased with himself for gaining a month, for the ease with which his plan unfolded, for tricking the birds into taking his test. But wise them all, with one eye open so the man would see only three sleeping birds, the crows conspired and conversed. Little whiffles, and shuffles of breath, imperceptible whispers and ruffles of jet black feathers, almost silent clickings of bills and they had it all worked out. The way in was the way out. They knew. How the cage was built. How the lock was clicked. Where the sun came from, so where the windows were. In the darkness Croci conferred with his confederation of three. They reviewed and renewed their hasty plan made in the woods. If it was food the man thought had trapped them, it was food they would take from the man to undo his trap. They would refuse his tricks until they were fed, up to the gullet line under their bills, until he was fed up of their silence and their turned backs of sleek black feathers. For four weeks they got fatter everyday until they feared their weight would slow their escape, so then they turned and looked at him, and complied, complicitous and contrite. He suddenly found them friendly, almost apologetic, ready to do as he asked.

So off they went. Each put in a separate room. Each given treats for pecking at some marks on a piece of paper. Each chatting to the next. Each knowing where the other ones were. Each saying to all, what each was doing. Cribbing. Cheating. Conferring and sharing notes. Each one in the exam room passing with full marks with the answers given by the one that passed before. They saw and pecked some shapes like bones. Curved bones. Square bones. Cursive bones. Bones alone and in pairs, nested and bracketed in repeating patterns of self similarity. It was easy. Funny little bones on white shiny sheets. They were the connoisseurs of bones. They were carrion crows. They came into this world nested in a nest of other crows. Each knew their place. A pecking order from birth. Their family group bracketed together. Each a word in a crow call sentence. They partnered for life. Their partner and them bracketed for life. First single then double quotation marks quoting ‘I do’ forever together. All chatter and clatter and calling names. All finishing each others croak called sentences. Each knowing what the other was thinking. Embedded, a single bird, in a family, in a pair, in a roost, in a rookery, in a flock, murmerating en-masse. One crow is all crows. Each lives in and through the other. Their life and living is made through self similarity. There is no plural for crow in crow. We is I is we. Palindrome and palimpsest, all words overwritten and undertaken by the rest.

So Croci and the crew were happy with their work. Or should I say holiday. A warm bed. Unlimited food. No predators. No men with guns. Simple tricks. Simple solutions. They made the law they lived by. Free. Rebels all. A parliament of crows. All for one and one for all. Croci and the crew knew the time and place to shew, to be gone. After the moon had rolled over her milky form three times, they would go at night. This was their plan. The man disappeared for two nights, three times, every moon turn. He had a shiny little bone he kept on a hook on the wall by the window. This clicked in the cage and made it open, but did not click to make it close. It remained by the window on them entering their cage. One night, after the games with the little bones on the paper, Croci landed on the man’s head and made him shout. An accomplice stole the shiny little bone when the man was not looking and put it under their wing. He shut them in and went off blustering and huffing on his two days off.

He returned to find them gone. The window open and the cage bare. They left, cursing and re-cursing man, the fool, the sucker, the feeder, the tester, the test they passed with ease. Way too easy for minds en masse. Each bird a word in the collective prosepoem that is crow life. The singular song. Of the flow of us Crow. One in all. Our call. We is Croci. We sing our name.

Begone wicked. We is gone.

About Three Cursing Crows

After the short poem The Song of the Crow, which was quite lyrical, I wanted more of a detailed narrative. The Song of the Crow was performed at a performance night in Carlisle and went down well. But there was a lot leading into it, as presented on my site, and to give it out alone and unexplained was interesting. You release stuff into the world and loose control of it, it has a life then, of it’s own. For a second thing I wanted be a bit more explicable, so wanted narrative, but with a feel of how Croci expresses them-self. I hope therefore that it is more self-explicating.

In the writing, rather than the idea of Croci being the either/or singular of it, he or she, I wanted to explore a collective unsingular, a they and a them. So in the writing to avoid pronouns Croci became what we call ‘non-binary’. But like bi-sexual, the descriptor ‘non-binary’ relies on describing the thing it is by saying what it is not. My belief is that this is a manifestation of the patriarchy and colonialism, an othering of a continuum in process, splitting of a whole into an us and them. The act of not assuming singular sexed pronouns worked to make Croci become both an individual and a collective, a hive mind.

So on this basis it was clear Croci had a clear plan before the man with the clipboard entered the wood. This is the power of the trickster and Croci became trickster with ease. The Trickster exists outside the closed court and kingdom of the King and looks in, enters and leaves. This is what I wanted them to do, to take the piss really. Narrative allows the scope for more detail to make the way Croci thinks and acts more explicable.

The title was worked over a number of times. I wanted to let the title point to recursion, so as to not talk about it explicitly in the story, and I struggled. Then I wrote the simple descriptor ‘Three Cursing Crows’ and the words showed me what to do through the string threecursingcrows. This to me is an example of the intelligence of material, even down to ‘reecursing’ being nested inside a thing not about recursing. Materialising ideas makes the materiality intelligent. Things act for themselves, all we gotta do is listen and look for their performance, pay attention, with intention and attitude, be available for outcomes, but not connected to them.

This story was quite descriptive. For my next writing about Croci I want to get more mythical.

The Song of the Crow

I is Croci

I sing my name

I is not me

I is we

I is all Crow

We all croak I

We rehearse

We curse

We recurse

All thee that are not Crow

You go

We flow

We flew

Liquid as the air

One river

Called Croci

One black Crow

One black flow

We go

We sing

The singular song

Of the flow of us Crow

One in all

Our call

We is Croci

We sing our name

About The Song of the Crow

The name Croci had been in my head for ages. Once, a few years ago it just popped into my head. It seemed the perfect start to a poem about the song of the crow. A crocus is a very colourful little plant which comes up in the spring, The name Croci worked for me, as it appeared to be the singular of a plural that was crocus. I liked that a black bird could have a name of such a colourful flower. That a black bird, a carrion eater, a scavenger, a bird with a croak for a call could identify with a delicate spring jewel seemed to suggest a creature unlike it’s public image, suggesting delicacy and an aesthetic sensibility. That the name of the crow was a declarative pun was also very appealing. Like a punch line to a dirty joke.

Taxonomically the corvids are oscine (singing) passerines (perching birds) and as such have complex voice boxes. The corvids, the crows, include, Ravens, Crows, Rooks, Jackdaws, Magpies, Choughs and Jays, the most colourful of the corvids are residents of the UK but there are over 120 species worldwide. In my writing I will use crow for corvid. Corvid is our linguistic Linnaean parsing of a life form that does not care what we call it. Crow is the vernacular. I can do taxonomy, just not in poetry.

That the calls of the crow, and all corvids generally are not songful and not always of a single bird, like a nightingale, appealed to me. Given what we hear of the corvids, the eponymous singularity of the ‘croak’ heard at a distance, once you spend time close to them together, you will hear the plurality of all sorts of little whiffles, chatterings, bill clappings and sundry noises, unheard at a distance. I believe the quieter calls are meant for other crows in a social setting. They are meant for kin not man. This suggests a private life.

For this poem I wanted to mix the plural and the singular, and I wanted a certain non-binary feel, as the sexes look identical. The individual birds identity would be inexorably linked to the group identity of a flock of birds who to non-corvids look all the same. The sexes are not expressed through different plumage. This, I felt, could reinforce the embodied and lived experience of the crow as bracketed, a thing within a thing, the one in the all. That for the research into crows, brackets were used, added a certain irony to the findings. In linguistics it seems bracketing is an important academic practice. In writing poetry I let the words speak for themselves, and play with each other and talk to each other. The repeated I, I, I, followed by We, We, We, seemed to come from the words being asked to do short repetitive utterances like a crows call. Then the repetition later dissolved into clamour of lines each with a different voice seemed apt.

In writing to a page, making the words seen, I noticed the ‘curse’ in recurse. So the way the corvids are seen as pests and vilified on farmland suggested an antipathy to the vilifiers, and possibly the glamorous, performing songbirds with elaborate and colourful plumage. Croaking as cursing was a great discovery.

The shift from ‘I is…’ and ‘I sing…’ to We is…’ and ‘We sing…’ from beginning to end, again, was suggested by the words themselves, and suggested a loss of the individual into a flock. The song of the crow went from all singing together to collective improvisation. So the words, once freed from my head onto the page, improvised too. The sky is the birds stage. The page is the words stage. The experience of the birds reified and embodied in ink.

This poem emerged like I hear the lyrics and sonics of rap. In rap I love the way in performance the words in one line change the words in preceding and following lines, through meaning and rhythm. When I spoke the song of the crow out loud it sounded like code-switching, so what was given by performance, was a capacity for being multi-lingual when you are taken for being sub-lingual, speaking a restricted code. Thus those willing to attend, hear a secret code, words of hidden experience, hidden in plain sight. So the birds blackness was not lost on me. We see them but don’t see them. Jim Crow, down by law.

I hear my local corvids differently now. Attention is focussed through intention and action to make art. When I go out the door to walk I step into their home. I step out now with more deference. Respect. I attend more. I say hello.

I felt like I had the song of the crow in verse, but I needed narrative, a story, to speak of their cunning. This is my next post – Three Cursing Crows

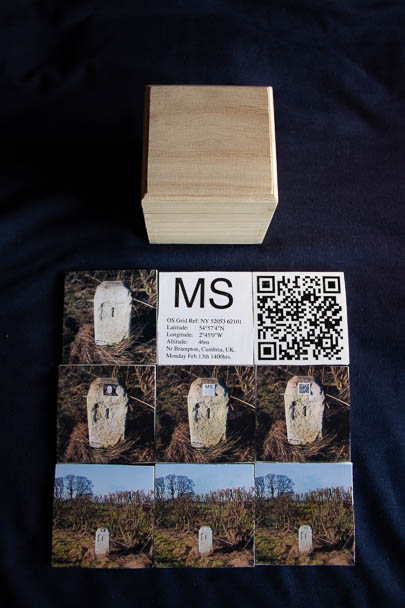

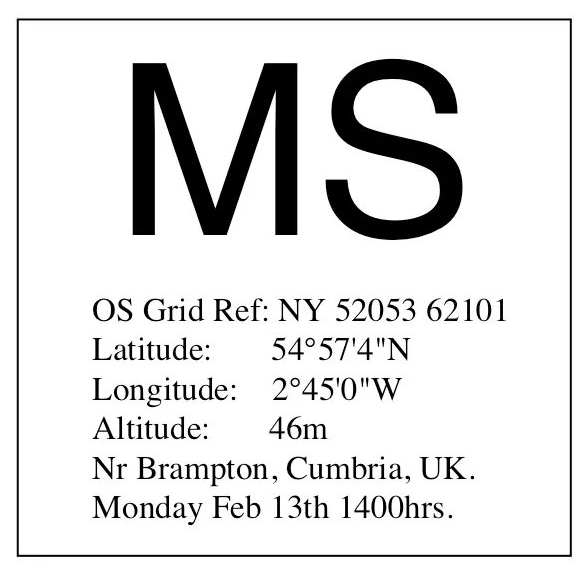

Brampton Ridge, Cumbria, UK.

Photo by Chris Reed

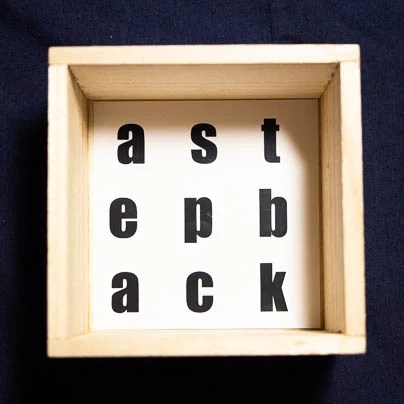

A Step Back

Where is

the thing

you are looking at?

Click an image above to see.

Click on centre white dot for Street View.

It is an object, an image, words and code.

It is on a hard drive on a server somewhere.

It is in your device’s memory.

It is in your body’s memory for a while.

It is many things.

That started with a step back from a real thing.

From a milestone in Cumbria UK.

And turned into a puzzle.

Things inside other things.

The image of the image.

i/i