Category Archives: Source Material

Posts linking to realted, useful and informative source material including work of practicing artists, theorists and commentators, research of anecdotal evidence, magazine or news items.

The Evolutionary Origins of Human Imagination

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

by Andrey Vyshedskiy, greatergood.berkeley.edu April 21, 2023

You can easily picture yourself riding a bicycle across the sky even though that’s not something that can actually happen. You can envision yourself doing something you’ve never done before – like water skiing – and maybe even imagine a better way to do it than anyone else.

Imagination involves creating a mental image of something that is not present for your senses to detect, or even something that isn’t out there in reality somewhere. Imagination is one of the key abilities that make us human. But where did it come from?

I’m a neuroscientist who studies how children acquire imagination. I’m especially interested in the neurological mechanisms of imagination. Once we identify what brain structures and connections are necessary to mentally construct new objects and scenes, scientists like me can look back over the course of evolution to see when these brain areas emerged – and potentially gave birth to the first kinds of imagination.

From bacteria to mammals

After life emerged on Earth around 3.4 billion years ago, organisms gradually became more complex. Around 700 million years ago, neurons organized into simple neural nets that then evolved into the brain and spinal cord around 525 million years ago.

Eventually dinosaurs evolved around 240 million years ago, with mammals emerging a few million years later. While they shared the landscape, dinosaurs were very good at catching and eating small, furry mammals. Dinosaurs were cold-blooded, though, and, like modern cold-blooded reptiles, could only move and hunt effectively during the daytime when it was warm. To avoid predation by dinosaurs, mammals stumbled upon a solution: hide underground during the daytime.

Not much food, though, grows underground. To eat, mammals had to travel above the ground – but the safest time to forage was at night, when dinosaurs were less of a threat. Evolving to be warm-blooded meant mammals could move at night. That solution came with a trade-off, though: Mammals had to eat a lot more food than dinosaurs per unit of weight in order to maintain their high metabolism and to support their constant inner body temperature around 99 degrees Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius).

Our mammalian ancestors had to find 10 times more food during their short waking time, and they had to find it in the dark of night. How did they accomplish this task?

To optimize their foraging, mammals developed a new system to efficiently memorize places where they’d found food: linking the part of the brain that records sensory aspects of the landscape – how a place looks or smells – to the part of the brain that controls navigation. They encoded features of the landscape in the neocortex, the outermost layer of the brain. They encoded navigation in the entorhinal cortex. And the whole system was interconnectedby the brain structure called the hippocampus. Humans still use this memory system for remembering objects and past events, such as your car and where you parked it.

Groups of neurons in the neocortex encode these memories of objects and past events. Remembering a thing or an episode reactivates the same neurons that initially encoded it. All mammals likely can recall and re-experience previously encoded objects and events by reactivating these groups of neurons. This neocortex-hippocampus-based memory system that evolved 200 million years ago became the first key step toward imagination.

The next building block is the capability to construct a “memory” that hasn’t really happened.

Involuntary made-up ‘memories’

The simplest form of imagining new objects and scenes happens in dreams. These vivid, bizarre involuntary fantasies are associated in people with the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep.

An interior brain structure called the hippocampus helps synthesize different kinds of information to create memories.

Scientists hypothesize that species whose rest includes periods of REM sleep also experience dreams. Marsupial and placental mammals do have REM sleep, but the egg-laying mammal the echidna does not, suggesting that this stage of the sleep cycle evolved after these evolutionary lines diverged 140 million years ago. In fact, recording from specialized neurons in the brain called place cells demonstrated that animals can “dream” of going places they’ve never visited before.

In humans, solutions found during dreaming can help solve problems. There are numerous examples of scientific and engineering solutions spontaneously visualized during sleep.

The neuroscientist Otto Loewi dreamed of an experiment that proved nerve impulses are transmitted chemically. He immediately went to his lab to perform the experiment, later receiving the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

Elias Howe, the inventor of the first sewing machine, claimed that the main innovation, placing the thread hole near the tip of the needle, came to him in a dream.

Dmitri Mendeleev described seeing in a dream “a table where all the elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper.” And that was the periodic table.

These discoveries were enabled by the same mechanism of involuntary imagination first acquired by mammals 140 million years ago.

Imagining on purpose

The difference between voluntary imagination and involuntary imagination is analogous to the difference between voluntary muscle control and muscle spasm. Voluntary muscle control allows people to deliberately combine muscle movements. Spasm occurs spontaneously and cannot be controlled.

Similarly, voluntary imagination allows people to deliberately combine thoughts. When asked to mentally combine two identical right triangles along their long edges, or hypotenuses, you envision a square. When asked to mentally cut a round pizza by two perpendicular lines, you visualize four identical slices.

This deliberate, responsive and reliable capacity to combine and recombine mental objects is called prefrontal synthesis. It relies on the ability of the prefrontal cortex located at the very front of the brain to control the rest of the neocortex.

When did our species acquire the ability of prefrontal synthesis? Every artifact dated before 70,000 years ago could have been made by a creator who lacked this ability. On the other hand, starting about that time there are various archeological artifacts unambiguously indicating its presence: composite figurative objects, such as lion-man; bone needles with an eye; bows and arrows; musical instruments; constructed dwellings; adorned burials suggesting the beliefs in afterlife, and many more.

Multiple types of archaeological artifacts unambiguously associated with prefrontal synthesis appear simultaneously around 65,000 years ago in multiple geographical locations. This abrupt change in imagination has been characterized by historian Yuval Harari as the “cognitive revolution.” Notably, it approximately coincides with the largest Homo sapiens‘ migration out of Africa.

Genetic analyses suggest that a few individuals acquired this prefrontal synthesis ability and then spread their genes far and wide by eliminating other contemporaneous males with the use of an imagination-enabeled strategy and newly developed weapons.

So it’s been a journey of many millions of years of evolution for our species to become equipped with imagination. Most nonhuman mammals have potential for imagining what doesn’t exist or hasn’t happened involuntarily during REM sleep; only humans can voluntarily conjure new objects and events in our minds using prefrontal synthesis.

The Power of the Blank Page

Rilke on Courage

Let everything happen to you. Beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Rilke

Rilke on Creativity -Article

Ada Lovelace on Creativity

i/i – A New Logo

The Image of the Image

i/i

This is the story of a journey and arrival at the making of a logo, a small and simple graphic representation of a much bigger and more complex thing. I can see the value in a logo to represent Moving Space. I use one already. WordPress lets you put up a small site icon to help give your site an identity. It appear where the url movingspace.art is displayed at the header of your browser. I use the Copyleft symbol. C Gnu.org, the home of free open source software says..

Copyrights exist in order to protect authors of documentation or software from unauthorised copying or selling of their work. A Copyleft, on the other hand, provides a method for software or documentation to be modified, and distributed back to the community, provided it remains Libre.

I like the idea that I put stuff up on my website, some my own and some other peoples, and you are free to use it but don’t claim it as your own. Credit the author, me or a. n. other. But more importantly make it part of a dialogue or joint venture. The image of an inverted copyright symbol expresses this better than a thousand words, but the words make it more explicit.

Part by design and part by chance I found a simple form which could become a logo without copyright infringements, which could function as textual and imaginal representation and connect art and science, mythos and logos, experiential learning and the arts therapies, and capture in essence what I am trying to do with Moving Space. I see what I do as a thing in process, an adventure, a thing in a state of constant self making, ouroborus, the snake eating its own tail. Recent research on the idea of recursion seemed to capture this and led to me seeing an idea I had already explored in a new light. To me this is the point of the exercise.

The image that emerged is this… i/i and represents the idea of the image of the image. I want to go on to more detail about the ideas that i/i connects together in another post but first I want to talk about the journey.

Long ago I read an article about an article about people and television. It stuck with me. The original article was from the 1990’s and in Christian Science Monitor and called ‘Behind the Glass’. It suggested that people were increasingly seeing a world behind the glass of their TV that some TV viewers judged to be better than life in front of the glass, in the living room, in their life. Thus they sought to emulate life ‘behind the glass’ so as to make their real life on their side of the glass more like the pretend life they saw behind the glass of the TV. The original article suggested this was problematic on the basis that much of the stuff they saw behind the glass was not real, it was manufactured in a TV studio or movie lot. The article about this article, that I read in the 2000’s suggested it had all got worse since the arrival of the internet on our computers. We could have seen this coming it said. Today the influence of life behind the glass of the mobile phone or tablet is similarly critiqued. Some say it is a grave problem, some that it is not a problem at all. I figure it is both. Images, like the imagination, can become a source of good and bad.

Imagination comes from the verb imaginari ‘picture to oneself’, from imago, imagin- ‘image’. This is central to what I am trying to do. To make art as a form of personal research. To make art and pay attention to what you make and what happens what you make it. This connects the arts therapies with experiential learning. In this an image, as a concrete object, a word, a poem, a painting, a dance move, your own or someone else’s can be used to make another image and thus act as a form of re-viewing or reflection or development of the preceding image. This is recursive or iterative. In this is also the idea of a mental image, in one’s imagination. This is the source of the thing you make as art, and the making, the embodiment, has a hand in this as well, literally.

I like working with projects and will usually have several overlapping projects on the go at any one time. I started work on a project I called ‘The Image of the Image’, connected to the idea started above, but ending with a person preferring their online image to their offline image. What struck me was the idea that the image people make of themselves online can, in some cases, become more attractive to them than the image they have offline. The politician sees the TV soundbite as more important than the thing the soundbite was meant to be about. But it became too generalised and unfocused.

It struck me that this idea, the image of the image of the self, was a problematic thing. For example it could be seen in an identification with the subjective projected image of self as opposed to identification with the body, the inhabited lived object that is the self. I became aware of concerns that there is a rising level of body dysmorphia in adolescents. Here and here. It seemed it could at some level to be connected to a relationship between the life lived in the embodied world of the here and now and the disembodied world of the internet going on forever. The suggestion was that it was a new thing.

It got me thinking about the myth of Narcissus. In one of a number of versions Ovid tells of a boy seeing his image in a pool, and fell in love with the boy he saw there but on this love being unreciprocated, turned into a gold and white flower, remaining rooted to the spot. In an earlier version, Narcissus spurns a boy, who curses him to fall in love with his self image in a pool and, because the image is unobtainable, Narcissus kills himself. This story is old, suggesting that it is nothing new. The Narcissus myth is a story of youth.

This appeared to me to be the story of the dangers of the image of the image, the disembodied image on the digital world being preferred over the embodied image in the analogue world. But in art making one is always working with an image of an image. The photographer Garry Winogrand, here said ‘I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.’ He sees an image on the street and photographs it. He is interested more in the image of the image than the image. Galleries are full of paintings, images of an image the painter had of the real world or in their mind’s eye. All images of images. I read a lot and the thing that is written is an idea about an idea the writer had. Be it an idea in a book about an idea about how a future world, set in 1984, could display the qualities of totalitarianism. Then I read Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, in which ideas were developed based on the ideas in Orwell’s book, the aforementioned 1984. Hockney painted ‘A Bigger Splash’ here expressing his delight at living in the California sun after living in Bradford. It is an exuberant image of the image of exuberant poolside life.

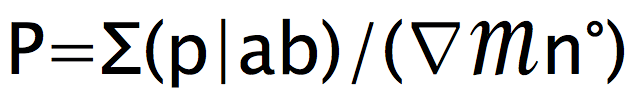

But is not just art. For a performance piece I did here I developed this Faux Maths formula to describe the algorithm for a walk.

Where P is the path of the walk, as an iteration or repeat of p, which is each leg as a straight line a-b until this is changed by meeting a person (the m is an aboriginal sign for a person, basically, the bottom mark left in the sand where a person was sitting) in which case the path p changes (the triangle) by n degrees. Although entirely fake as maths, I wanted this to be a symbolic representation of a walk. In my walk on January the 1st I also used a very simple version of this, an algorithm sending me LLLR and ultimately into a closed loop. Maths contains symbolic forms called numbers and formulae. Maths, language, art, all are symbolic. All contain elements of repetition, images of images, ideas about ideas, things referring to other things or nesting within things.

At the end of the last post I encountered contact with the capacity for crows to engage in recursive reasoning. This piqued my interest and I wrote about recursivity in experiential learning and commented on it’s occurrence in a wide variety of settings. In maths recursion featured in a maths controversy. A book was written called Principia Mathematica attempted to prove all arithmetic from basic principles. But a mathematician called Goedel proved using maths that there are mathematical statements that are incomplete ‘that are true but unprovable, and perhaps even more surprising, that said the system of axioms will lead to a proof of its own consistency (lack of contradictions) if and only if it is itself inconsistent.’ Here. So a form of recursion was used by Godel in his ‘Incompleteness Theorum’ which could prove itself true by proving itself false through an act of recursion by referring to itself, a thing considered heretical to maths. And you thought modern art was weird.

The research on recursion proved very fruitful. Some of it was quite demanding intellectually. I reconnected with maths and came to see it as a language I could understand. I started to see recursion everywhere. In accounts of consciousness. In accounts of creativity and imagination. In accounts of human and animal evolution. In the simplest and most grand acts of art making, in the works of great literature and music and Fine Art, in performance and theatre. It was intrinsic to experiential learning. It was central to infant development and attachment. I came to believe it was central to human evolution through attachment and teaching and toolmaking as an inseparable trinity of familiality, sociability and teamwork. It is a way of seeing things as being simultaneously both single entities and things in process, naturally developing hierarchies of complexity providing simultaneously a global and a granular perspective. I think it can spin tales of fascination, creation myths and literature, create mathematic formulas that allow us mastery over the material world, enable music that will make you weep, it can move matter.

But it was also to be seen in ideas about echo-chambers on the internet and in conspiracy theories and in accounts of totalitarian systems. It could be seen to feed into the inter-generationality of abuse. The easiest way to become an abuser is to have been abused. But it can spin tales of deceit, make men and women dance on tables in the Capitol on January the 6th, and send people to the gas chambers. Recursivity can produce infinite loops from which there appears to be no escape. Cancer could be seen as a form of recursive growth. Unending. Extinguished by death of the organism. The climate emergency a form of cultural cancer. The myth of unlimited economic growth. Extinguished by the extinction of the human line.

I saw this on YouTube. By William Burroughs…

And that line ‘…evolution did not come to a reverent halt with the arrival of homo sapiens…’ stopped me in my tracks. So very funny. So very true. I became interested how this idea might work through a serialised story at a poetry night I attend and started writing and through developing the story I came to see this fictional scenario was actually worryingly realistic and that this may be the inevitable outcome. The story remains unfinished. It frightened me. Maybe the Earth wants rid of us. The Goddess in the story is driving global warming to rid the world of man. There are some interesting ideas about that suggest fiction is a way of working through ideas about the big issues that facts and figure fail to achieve. Wagner is good for gender issues, Orwell for the politics of totalitarianism, Marquez for the crossover between magic and realism.

In the story I worked with the goddess as the one facilitating the end. The Goddess says to Eva the human protagonist…

“I am not who you think I am. I am not lightness and sunshine. I was once but I am no longer. I am Eumenides, I am Athena, I am Banshee, I am the Furies. I am the Maniae, I am black Kali the destroyer. I am Ran the Giantess of the ocean. I am Hel the Queen of Death.

I am the perpetrator and purveyor of global warming. It is my act of homeostasis. I bring global genocide, infanticide, regicide, patricide, sapiocide. I want the end of man. I want man cooled and comatose. I want man unevolved and extinct. I want man dead.”

And creativity and imagination is, I think, behind it all. It is our curse and our blessing. We can imagine unlimited growth but not how to prevent it becoming cancerous. Recursivity is many things, but I have come to believe it is central to our imagination. Our imagination is limitless, unbounded by the material objective world. This makes it at once liberating and dangerous. I came to see i/i as a symbol of imagination. The ability to make an image of an image, make an idea from an idea. But unbounded imagination is problematic. We can get lost in such a vast world, believe the world is flat, or that Trump won the election or that we can ‘Take back control’ or that nobody will notice if people put vast numbers of people into camps to be ‘re-educated’ again. I can get lost in thinking about thinking, writing endless blog posts that nobody reads.

Through my discursion around recursion, prompted by an article about how crows are a clever as people, I have found a way that makes all my wanderings make sense. But that sensibility is subjective. It works for me. Recursion is a form that cannot be expressed as one word. At heart I am a nominalist. I have come to realise that all we experience are symbols of some deeper reality. Words point the way but are never the destination. The path is made in the walking of it. The map is not the territory.

A favourite quote of mine is from Orson Welles who said “The absence of limitations is the enemy of art.” My hiatus filled with reading and art making related to recursion has acted to put some brackets around the overly open and discursive path of the last few years. Like my self-imposed and entirely amateur and anti-academic PhD has ended. Oddly on my 65th birthday. My plan, stated at the end of my last post, to work with artform to explore the experience of exploring recursion has taken longer, and generated more words than I expected, but has been fascinating. All I have to show is a new logo of bracketed imagination, but getting there has been fruitful, and instructive. The symbol, the image, the imagination, is everything. One picture is worth a thousand words, but without the words there would be no symbol. The symbol emerged from a long journey. So it could also be a symbol for adventure, the thing that happens before you arrive. Art is a journey, a thing in process, made material momentarily by the flash of an image, a painting or a poem left on the trail to show the traveller where they have been. So i/i may change but for now it works. I will ramble on.

Not all those who wander are lost…

Tolkien

Header image courtesy of thisisnthappiness.com – ‘art. photography, design, dissapointment’