Artist and teacher Kit White offers a toolkit of ideas and a set of guiding principles for creative thinking.

A good article about art as a way of thinking about the world.

Items about all forms of art and art-making

Artist and teacher Kit White offers a toolkit of ideas and a set of guiding principles for creative thinking.

A good article about art as a way of thinking about the world.

Last night at bedtime I was reading John Cages’ book ‘Silence ‘ here.

He was writing about the art of Robert Rauschenberg here and I came across this quote…

The paintings were thrown into the sea after the exhibition. What is the nature of Art when it reaches the sea?

John Cage – Silence p98

I intended to read more, but that idea was so good I decided to sleep with it in my head.

The idea of going to see art in the sea.

Sea art.

This post is a link to a very interesting article, describing arts practice as a way to practice finding a healthy balance between chaos and predictability. Mark Miller, a philosopher of cognition and research fellow at both the University of Toronto and Monash University in Melbourne talks about the human brain as a prediction machine. The source, VOX, has as its strapline ‘Your mind needs chaos – The human mind is designed to predict, but uncertainty helps us thrive.’ In the article Miller proposes that mental health needs some chaos, and art making can healthily provide that chaos.

The article summarised

Being able to predict what happens in the world is useful. We have a system in our head that seeks to predict what happens in the chaos of the world which upon experiencing this chaos feeds back to modify the model so that it can then feed forward to guide our behaviour. This is the recursive act of learning from experience, or not. If we don’t learn from experience we can become overly fixed or overly chaotic in this process and thus become unwell. The proposal is that viewing and doing art both provide an experiential arena where we can practice the skills of managing our encounters with chaos.

Arts materials like words, paint, musical notes, wood, stone and movement are in an unstructured or chaotic form when we encounter them. In creating form as art makers we learn to make form out of what starts as unformed, but in doing so some new or unexpected or chaotic element makes itself known. We take things we think we know and see them in a new way. Form and chaos coalesce.

Me summarised

The header image shows grass responding to its environment. I worked for an events organiser and mats put down for a wedding overlapped and removed the light so the grass stopped photosynthesising. One layer of matting let enough light through for the grass to photosynthesise. In my art making I end up with an embodied account of my experience. This image immediately struck me as an embodiment of the experience of the grass.

I found this very exciting like the grass had become an artist. It filled me with wonder and awe in a way that kind of freaked other people out. I do genuinely believe my awe at seeing the experience of grass was a result of my persistent and consistent exposure to art making.

In viewing and doing art I am consistently in awe at seeing some new thing I have never seen before. It might even be a thing I made. Yet the awe emerges out of the most mundane things, paint, pencil marks, and poetry as just organised words we speak every day. It is like through art the intentional exposure to uncertainty and unpredictability teaches me to be able to see new possibilities. And not only that, but to know that I know from my experience of art making, that I will see new possibilities in both chaos and mundanity. This is I think, the wellbeing the author and article refer to enacted and rehearsed through the act of making art.

The link below will lead to the original article on VOX, which in turn leads to the original podcast.

Sometimes it takes a long time

But be not afraid or downhearted

Like the Celtic day, starts at dusk

And their year, as winter starts

Growth begins in darkness

And, disembodied,

A growth contained

In an others body

A cell

Then two

Then four

Geometric progression

Grains of rice doubling on a chess board

Until a space is filled

The Blastosphere

A yoke sack, an anus and a mouth

A literal visceral vesica pescis

A vessel

A fish

A body of water in water

A boundary and nothing more

It is, and is becoming

Some thing

A boy

A man in body only

In me is spirit

Sexless, disembodied

I don’t care about my pronoun

I am it, he, we

I am legion

I am no thing

Nowhere

And everywhere

My body lets me speak, and act and reproduce

But I am discombobulated, dissociated

Disinterested really in bodies, even my own

And, enjoying inhabiting this mans body yet

I would love to inhabit a woman’s body

Or a fish or a cloud or a body of water

To find out more about consciousness

To remember, after being a mole

About being blind in blackness digging in my garden

So instead I embody things in

The intelligence of materials

Paper, or ink, or words on a page

And speech

To make the air vibrate

In your ear.

This was written for performance. It was a thing that fell out of me and was very personal and was quite an important trail marker on my art as an adventure and research trail. Often artform preempts material emerging into consciousness. It kind of acts like an alchemical process and distils down lots of raw material then allows the product to float up to the surface. In art making this is sometimes called percolation. I call it incubation. But different words for the same thing. Regards this website, it says a lot about what art as research feels like. Regards me, it revealed some personal stuff that was emerging for me.

It is also about poetry and art making and what art therapist Pat B Allen here and here calls, spiritual technology, the latter descriptor being consciously and deliberately and accurately oxymoronic.

As performance, the poem was designed to be heard and not read. So below is the poem as spoken word.

Gestate

This post is a complement to the previous post here about the physical and emotional response to viewing great original art. We could say art is a collaboration between our phenomenal and emotional world and as such, as sentient beings, one would assume this may have the capacity to connect with us phenomenally and emotionally. In simple terms, it can move us. The last article about scientific evidence of the impact of seeing an original painting reminded me of a track by Idles, shown below which is a tongue-in-cheek defence of being moved by art. Stendhal Syndrome is a description of a reaction to viewing art in which a person faints or becomes delirious. It is named after the writer Stendhal. The man with the beard moving through various art galleries is Adam Devonshire, Idles bassist.

In 1817 Stendhal had a visceral reaction to being in Florence surrounded by exquisite art and architecture.

He commented “I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations . . . Everything spoke so vividly to my soul. Ah, if I could only forget. I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call ‘nerves’. Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.”

The syndrome is not a diagnosable illness but is a phenomenon described by an Italian psychologist in 1979 based on their experience of tourists responding to art, particularly in Florence.

In an article in The British Journal of Psychiatry by Gary Woods here Joe Partridge, songwriter and singer for Idles is quoted as saying that an experience in a Valencian gallery in Spain, rendered him awestruck, tearful and ‘captivated to the point of nausea’.

When I lived in London and visited the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery regularly I recall having a strong emotional and embodied reaction to seeing the actual brush strokes of artists like Monet and Turner. It did make me feel lightheaded like I was going to swoon. It surprised me.

Maybe the difference between the painting and the reproduction is the knowledge that one is witnessing the embodiment of the moment the paint was put on the canvas. In a reproduction, one cannot perceive this. The experience of seeing the reproduction is lesser, in that knowledge accompanies sensation and perception that tells you this is a copy of many copies. The original seems more like a live experience.

Joe and Idles value the live experience and in this video below towards the end, Joe is overwhelmed by the experience of being there. Enjoy this astonishing performance.

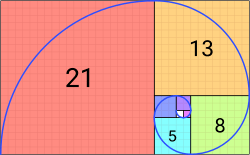

Researching recursion brought up a lot of references from a range of sources. I worked my way through them. Intuitively there seemed to be connections centring on the idea of self-similarity, a function that expressed itself by referring to itself, like a thing that made itself, like way experiential learning and art make themselves. There was a lot of maths, code, logic, and some geometry. I wanted to start to explore recursion by making something, so geometry seemed a good place to start. I decided to start by making a thing called the Golden Ratio as a thing that makes itself. As the quote below from Wiki indicates, the study of the Golden Ratio has spanned millenia.

‘Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties. … Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics.’

Mario Livio — The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number.

I cannot do this material service so the Wiki entry is here

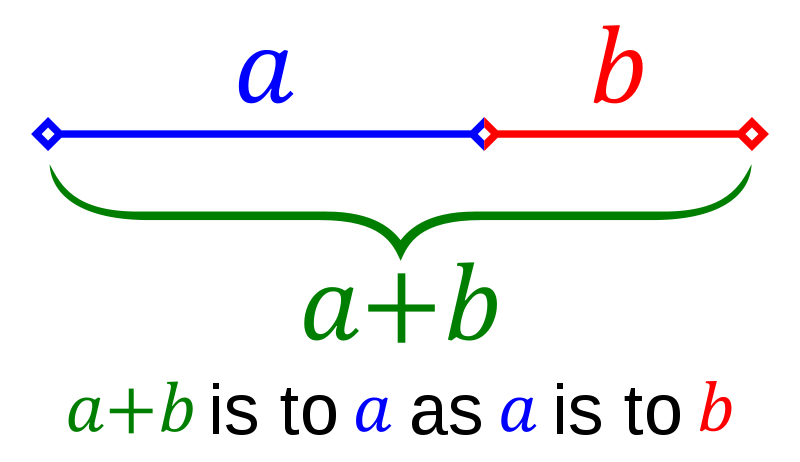

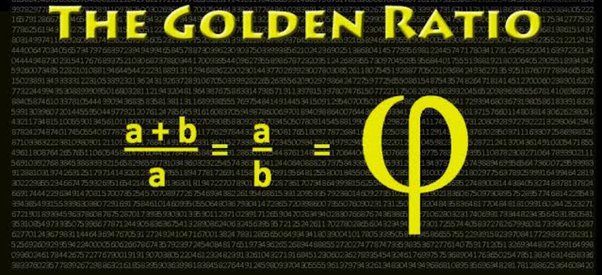

But first a bit of maths. A ratio is a thing that exists only as one value as expressed in relation to another value. It is one thing divided by another. 1 divided by 2 is a ratio. It is 1/2, a half. The golden ratio is a mathematical and geometric expression of a particular ratio. As a ratio, it is described as (a+b)/a=a/b where a and b are numbers.

As a geometric form it is expressed thus…

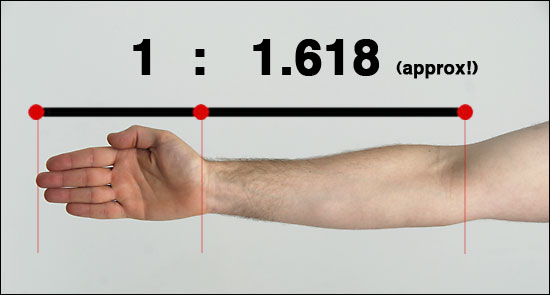

As a decimal number is it 1.618033988749…. so it is an irrational number, it goes on to infinity. The ratio is the same for 1 and 0.618… as it is for 1.618… and 1.

But as many sources show, the golden ratio is also a thing that exists in nature.

It is also a thing expressed as a mathematical symbol, Phi, a letter from the Greek alphabet.

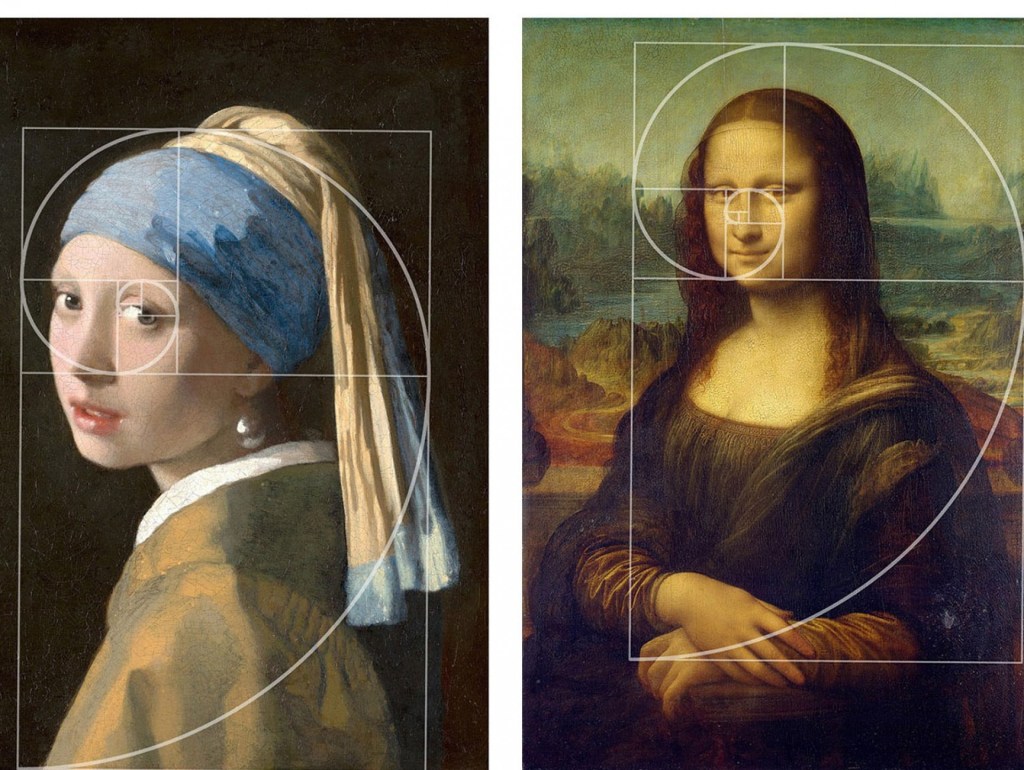

It is also the basis for a mathematical phenomenon called the Golden Spiral which expresses a thing called the Fibonacci Sequence found in art and nature and mathematics. It can be expressed in many ways.

The Golden ratio is recursive and as such seems to reiterate the feeling of researching recursion. A feeling of finding some deeper connection between things, between experiential learning, art-making, crow intelligence, coding, philosophy, on and on. It feels like all the different references may emerge from a single or underpinning referent. This interests me. But this was all a bit abstract. It also evoked a feeling of caution, like I was maybe seeing things that were not there, things not connected. I wanted a more concrete experience. Something embodied not just imagined.

You can make a Golden Ratio with nothing more than a pencil, compass and ruler. I decided to make a golden ratio for myself. My intention was to have a concrete experience of making it rather than just having the abstract experience of thinking about it. I was already exploring the recursive behaviour of crows through poetry, and this changed and deepened my connection to them. So I set out to draw the Golden Ratio with a pencil a ruler and a compass. As shown above, there are a great number of discussions of, investigations of, theories of, and expressions of, the golden ratio by very learned people spanning millennia. This does not really interest me. Google Golden Ratio and you will get many varied references thus…

My idea was that the golden ratio has something to do with recursion, which has something to do with making art and experiential learning and this interests me. All the serious ideas generated by other people can help me pursue this interest in ways my brain could never imagine, like Fine Art made by proper artists can help my art-making. But most helpful is the art I make. My intention was to simply make it and pay attention to what I make and what happens when I make it. As always. Don’t Google it do it yourself, the punk ethic. My preparation was to get hold of a big compass and a joiners pencil. I use wallpaper lining paper. It is a heavy gauge 300gm/metre weight paper like fine art paper, but a nice off-white and is as cheap as chips. It remains curved off the roll so needs to be fixed to a board with masking tape. This also fits with a punk ethic. So I made it myself. I went into action.

I found some instructions in a book I got from a charity shop about making the golden ratio1. I bought the big plastic compass from Amazon here. But this proved a bit bendy. My arcs drawn were a bit wobbly and uneven. So I did some practice on another bit of paper and found a way to make a nice steady arc. I got my ruler and joiners pencil. I photographed my making of it…

Or click here

It proved bizarrely nerve wracking. Hippasus of Metapontum was reputedly drowned at sea by the Pythagorians for discovering irrational numbers here, and according to wiki ‘Irrationality, by infinite reciprocal subtraction, can be easily seen in the golden ratio…’ I hoped Pythagoras and the gods were not watching.

I measured the two sections of the golden ratio I made and did the maths to see how accurate I was. I was not drowned at sea. Nothing happened. I drew a line with two segments of differing lengths. It seemed mundane. What was I expecting? I let it go and let it incubate, or percolate, whichever you prefer. I went to work. I made other art. The board with the line on sat on my desk for ages. I lost my measurements done at the time of making. So I returned to the drawing and the following measurements were taken.

On measuring this, the two segments were 22.3cm and 13.7cm giving 1.62773723. The longer segment divided by the shorter segment should be 1.61803398. So this can be applied to the sides of the triangle I drew, so (22.3 x 13.7) / 22.3 = 1.61434977, this applies to the bottom and side segments of the triangle. This gives an error of about 0.009, mostly due to my hamfistedness and a wobbly compass. I was pleased with this outcome. It is interesting that the Fibonacci sequence moves towards 1.618… with each iteration of the recursive sequence. My second iteration was closer. Maybe it was just noise error. It seemed mundane and magic all at once, which is what magic and reality really are. Perpetually dichotomous. Certainty is certain in its uncertainty.

I did lots more reading about recursion. Eventually, I reflected on the experience for this page. This is my reflection.

My immediate reflection after standing away from the image for a while, was that the further you stand from the mirror, the smaller becomes your image, but the setting gets bigger. Whilst there are no unequivocal written accounts, it is suggested that Plato knew about a mathematical phenomenon that went on to be named ‘The Golden Section’ by Martin Ohm in 1826. But the (a+b)/a=a/b formula was written in Euclid’s The Elements 2300 years ago. Maths has moved on a long way since then. My understanding is that maths was then, more of a geometric thing. It was understood as objects, albeit in many senses imaginary objects, it was also in a real sense about things you can make and draw.

Making this object put me in some ways back in that time. The line drawn and segmented could be any length, and the segments, with simple tools, could make an object that made itself. All the actions root back to and emerge out of that line. Then that line produces a form which relates only to itself. I could see how Plato could be Platonic, how he could contemplate pure form which could transcend or sub-ordinate matter. To make the golden ratio, on reflection, was at once transcendent and mundane. The act was mundane, but the emergence of a thing that made itself, utterly without any other referent in this world now seems quite remarkable. It reinforces my belief in nominalism. That all that is written about the golden section are just signs pointing to some thing that exists outside of our experience, and this thing is mundane and transcendent. I can see why Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans felt like they were in touch with some deeper reality. And all it is is a pencil line on a piece of paper.

This reflection also puts me back again in a place I have been before. I have an image of a path, in partial darkness, by some garages near my home. I was doing a series of algorithm walks, llr, rlr, rrrl, etc to make my daily wellness walk more interesting. At some point, I realised that each walk was an act of creation, unique and unlike any other walk I had done. Because the path was varied, but because the time varied, I did just this walk, just today, it could never have been done tomorrow or yesterday. I was strongly struck by the realisation that creativity is mundane. We make a sandwich, we drive to work, we make stuff happen. But through connecting to the innate creativity in the seemingly mundane act of making a sandwich, watching endless TV cookery programmes by celebrity chefs showing me how to make a sandwich become mundane.

The act of making the mundane into art, finding some deeper structure in drawing a line and forming a ratio, has risks. If it can render everyday life mundane, it risks becoming escapism, the evasion of everyday life. For some reason, Irving Welsh sprang to mind writing about the risk and trap of escape. The film version of Welshe’s Trainspotting starts with a great, but disturbing diatribe on the seemingly simple escape from the complexity of life…

‘Make a choice…” I think. I did not, like Renton and Iggy, choose some external internal stimulant, although in the past it was a choice I made, it made me unwell, so I made art, eventually after periods of unwellness that showed TV shows and stimulants to be singularly unstimulating.

So like the Glorious IG, I moved on and chose not to “Choose Life; Choose a job; Choose a career; Choose a family…” or at least I chose to be more choosy over what I chose. The lines at the start of the film are highly ambiguous. Iggy Pop sang about a lust for life. Maybe that was what drove Renton to become a junkie as a way out of the mundanity of his diatribe. Renton chose junk, but it kind of becomes a cypher for an escape from choosing ‘…a f***king big television,’ and ’stuffing f***king junk food into your mouth’ as acts of self-destruction which can be ameliorated by recognising the mundanity of self-creation, making art with a pencil or a walk on a morning past a neighbours garage as opposed to shooting up. The line as a walk or as a pencil mark is transformational. Making them is the key. It is not the same as reading about somebody else’s walk or seeing somebody else’s line. But the purveyors of f***king big televisions and f***ing junk food don’t want us to know that. They want us to buy, to buy into a drug of choice, TV, food, holidays, hair products, an online persona, booze, weed, speed, junk, to take Soma, the drug of choice in Huxley’s Brave New World. In an article from Medium by Yash Deshmukh the author explores Soma as a metaphor for current experience, not a future society. The content of Renton’s rant is the drug. Consumerism as Soma. Work to earn money, to buy things to help you escape the mundanity of working to buy things to help you escape… The endless loop. Recursion as a closed loop is a risk. But the recursion of making the golden mean feels different.

I am still working on how recursion as creativity, exposing deeper forms, and recursion as an endless infinite loop reinforcing the same shallow forms of mundane life, differ. I am still working on what it is about making things as art that makes the content of Renton’s rant mundane, but the experience of drawing a pencil line on paper becomes rich and revelatory. Am I mad, or is the world mad? I will make more stuff as art as research. The journey goes on. The path is revealed by the walking of it.

Artwork by Chris Reed