A Basic Experiential Learning Model

The basic model that formed the basis, I first encountered in 1985 at Outward Bound, described learning as an active process which used reflection on experience to feed forward to guide more action. Learning here is taken as a change in behaviour. We worked with the model as the ‘Plan – Do – Review’ model. You do something and think about it with a view to learning something to help you do things better in the future. We aimed to facilitate experiential learning to help people to do some task better as a team and as individuals according John Adair’s Action Centred Leadership.

There are other models of experiential learning. Notable is the model of David Kolb, and any work by Colin Beard is particularly useful. An article making comparison of Kolb and other models is available here.

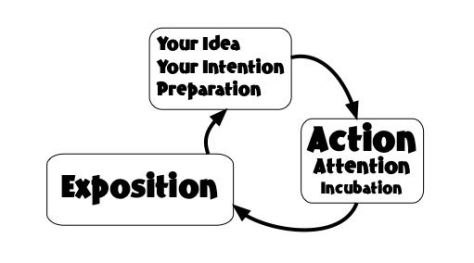

Through arts practice I developed my own model based on plan – do – review. As a simple circular learning model, this works well as a heuristic, general enough to be applicable to many settings, such that a specific application and development may emerge for and from that setting.

The arts-based experiential model I want to show below was developed out of a basic experiential learning model and is one of many models of how to do art as experiential learning. It is presented as one way of doing art as research, and it is the one way that works for me. Like all models, it is incomplete. A model is a map to guide an exploration of a territory that is always ‘..too complicated to allow anything but approximations’ to quote mathematician John von Neumann. You and your work is the complicated territory, and you will find your own model by doing the work, making art.

This makes it a bit like creativity. Creativity is difficult to teach and explain, but can be learned and understood. But this comes through the experience of doing it, not by being told or taught how to do it.

This is the model I use to guide my art as research. It may lead to some truth or knowledge, but that will be subjective, situational, emergent and diverse, even dialectical. My belief is that art as research is suited to subjective, situational, emergent, diverse and dialectical situations, on it’s own or as an adjunct to quantitative and qualitative research. You find what works for you.

Introduction of the Art as Experiential Learning Cycle

A specific sequence emerged for me out of art therapy and experiential learning applied to my personal arts practice, and led me to the idea of art as research, and it goes thus..

Ideation

Intention

Preparation

Action

Attention

Incubation

Exposition

Ideation is about just having an idea in your head about something you want to make as art. It is a starting point, but it also comes out of your art making and feeds back into your work. Your ideas are seeds that makes your work grow. Intention is an act of intending to make something as art to research experience. Preparation is the act of getting ready to make art. What materials do you need, what do you need to practice, what more do you need to know before you commit to making something as art. Action is the act of making. In this you pay attention to what you make and what happens when you make it. You also may find it useful to take a break to allow incubation, to let the seeds of ideas grow on their own. Exposition is the act of exposing what you did and what you made as art to yourself as witness, or showing your work to others as an audience. Exposition is more than exhibition, just sharing or showing, in that it may help your research to show some working, what you did and why you did it. Exposition is entirely subjective.

But this process is circular and emulates the simpler plan-do-review cycle but applied to art making as research, it goes like this…

Development of Modified Art as Experiential Learning Model

It is proposed that this model may be used to develop personal art practice as a form of research to explore and express personal experience, and this may enhance the health and well-being of the art maker.

Although it is not always encountered or used as a reiterating sequence, as a sequence it goes..

Ideation

What if you can’t think of any ideas?

If you want to make your own art, stealing other people’s art is a good place to start. Austin Kleon wrote the bestselling book ‘How To Steal Like an Artist’ here as a book on his website, and here as a TED Talk. All artists steal. But French New Wave film-maker Jean-Luc Godard summed up how to steal by saying, “It’s not where you take things from, it’s where you take them to.” If you don’t think artists steal, here is a collection of artists’ quotes from Kleon about stealing. This one struck me as apt: “If you steal from one author, it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many, it’s research.” — Wilson Mizner.

In arts education, it is called ’Source Material’.

Source material is everywhere. Visit my Tumblr newsfeed and join Tumblr if you want more. Use your Tumblr to accumulate your own sources. YootYoob is full of arty stuff. This thing below on John Baldessari brings together two of my art heroes, John Baldessari and Tom Waits. John Baldessari, in relation to the question ‘Why is this Art?, simply asked ‘Why is this not Art?’ This question is important here.

If, as I assert, art is anything you make, as long as it is art, then you can make something and call it art, but exposed to scrutiny of other people, it may be useful to have some idea what you mean by art, so it might be useful to pay attention to ‘Art’ in it’s broader setting. Attending to what and why you steal from real ‘Artists’ can help you decide why your art is also ‘Art’.

Intention

This is a big part of the art practice, even if you intend to have no intention. You intend to make or do something as art. Intention is about what you want to do, ideally, what you want to do with your idea.

An ‘Artist’ is expected to have an explicit intention for their work and seek ways to express this intention. For an artist, that intention will have to account for the work being seen by an audience. It may be assumed that people viewing the work will find in the work what they will, irrespective of the artist’s intention, or that as an artist, they need to be explicit in meaning such that the viewer in the audience will explicitly ‘get it’. For more on this idea, see here.

But with art as research, this approach to intention regards an external audience as less important. You are the audience to your own making. It is the act of attention that is the intention. Your intention is to experience making art to be able to explore or research experience.

What if I can’t think of an intention?

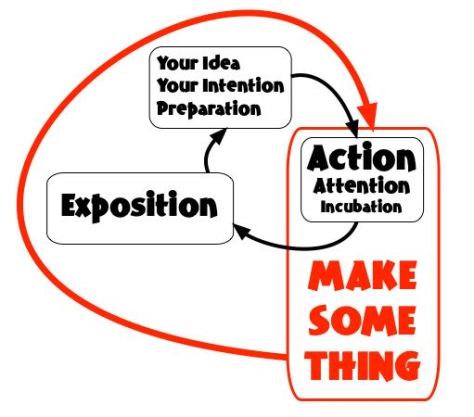

Like the discussion above of not having any arty ideas, if you have no ideas about your intentions, skip the intention section and go to action. If you are not sure how to have an artful, or researchful intention, just make some thing as art and see what ideas emerge and let these ideas grow some intention. Making stuff is the important bit. So below, for anyone unsure as to where to start in this cycle, ignore the cycle. Don’t sweat it. Make some thing and see what happens.…

…the rest will follow. Making makes momentum.

The idea and intention to just make some thing to see what happens is very powerful as a starting point or as a place to return to often. It can and will transcend your art making into making your everyday life a creative act.

So, over time, intention here may include choices about form and content, what materials you want to work with and what you want to say with these materials. Intention may be guided by interest in or inspiration from the work of some established artist. What I am suggesting is that over time, your ideas and intentions will develop some degree of continuity. Your experience of art making will make known to you, aspects of your experience that interest you, or challenge you, or surprise you.

How does intention relate to art as research?

In formal research, ideas and intentions could be seen as your ‘Research Question’. Like a research question, ideas and intentions may involve ideas about context, process, materials, or it may intentionally be very open and undecided. It is useful to write an intention, forget it, and return to it in exposition. What you see on return, what you see you have attended to, is a powerful research tool to help guide your next turn around the cycle. What you attend to is your own experience helps you better attend to your own health.

An artist and art therapist who has done great work on intention and attention is Pat B Allen. She developed and works with Open Studio Process as a therapeutic medium. In this the basic plan do review format is expressed, one makes an intention for art making, makes art, then reviews the experience and shares what is found.

Of intention in making art for health, she writes, ‘Intention is a way to ground and settle and prepare to receive the image, which is the medium through which we communicate with the deep knowing that resides within us. We strive to simply notice what comes up and let it go, allowing the image to emerge rather than attempting a predetermined outcome. Once we begin to make art, we set the intention aside. Beginners may make an intention such as “I enjoy making art” or “I relax and get in touch with myself.” More experienced practitioners may ask for guidance around a personal issue or life circumstance. Over time, intentions grow out of the relationship each artist has with their images1.’ The more work you do, the more your intentions will emerge and form a pattern.

Your image, the art you make, is your experience. An image can be some thing you do as much as some thing you make. In approaching your art making as personal research your art making develops your relationship with your own experience. In short, intention provides containment and momentum to your research of your experience.

Intention is followed in the round by preparation.

Preparation

This is the bit you do to get ready for action, the making of art. It is simple and needs little description.

At its simplest, you may decide to do no preparation except collect the art-making materials you need. Or if the art making is more of a performance, a doing more than a making of a thing, you may simply prepare the space.

For me, I walk a lot as art making and treat this as performance. For this, preparation is checking the weather, getting my gear ready, checking the route and letting people know when I will be back. I did a couple of walks in which on one, I took no digital devices, so no phone, navigated with a map and compass and wore a clockwork watch, just taking some drawing material. On the other I had a mobile and a digital SLR. I simply researched how this impinged on my experience of the same outdoor space.

Preparation may include getting materials ready, practising some art-making technique, doing research in books or online regards some aspect of form or content of my art making. It is a way to enter the action phase such that one may concentrate on fully inhabiting it as an experience.

Action

This is the key phase. You make some thing as art and pay attention to what you make and what happens when you make it. But how to do this? How can you, as a non-artist, (if that is what you think you are) make art?

If I make art, how can I say to myself, ‘This is art!’?

In my search for sources regards art as a verb rather than art as a noun, art as the making rather than the thing made, I found a great article by Irving Lavin, art historian, from 1993, in which he describes 5 Assumptions about what a person does to a thing to make that thing as art. It is not in the materials or the setting or the techniques, but it is in what the artist makes these things do. He says

1 Anything man-made is a work of art, even the lowliest and most purely functional object.

2 Everything in a work of art was intended by its creator to be there.

3 Every work of art is a self-contained whole.

4 Every work of art is an absolute statement.

5 Every work of art is a unique statement.

Lavin is as a professional historian required to ask ‘Why is this Art?’ and say with authority, regards some object ’This is art!’. The five assumptions he makes can be applied to your work. If you look in the art world, everything and anything has been made as art.

The first and second ones are easy. You can make anything as art as long as you put it there intentionally. This is a good starting point.

The last one is easy too. Whatever you make has never existed before you made it as art. Even if it has ideas from elsewhere, your configuration is unique. This is called poiesis, the bringing into existence some thing that has not existed before.

The third and fourth are useful in deciding whether this is a ‘good’ work of art. In ‘Fine Art’, these two are present in art that resonates with audience and viewers. And whilst the capacity for resonance will vary from person to person, and whilst some artworks resonate like a bomb going off, it is a thing that will develop the more art you make. Each artwork may vary in its resonance, but some will go off like a bomb for you. And what your art does for you is the point of art as research. Later, after action, in exposition, these two assumptions may be good things to attend to.

The full article is worth a read and is available here. I wrote a post about this, which explores this in more detail here which talks about making sandwiches as art.

Lavin finishes his first assumption with ‘Man, indeed, might be defined as the art-making animal, and the fact that we choose to regard only some manmade things as works of art is a matter of conditioning.’ Part of the idea of making art as research is to undo that conditioning. This supports Baldessari’s question, ‘Why is this not art?’ In making art the way you want to make art, in undoing that conditioning regards what is art, you may undo that conditioning regards what is you. The art is the experience.

In all this, there are no objective definitions or truths. This is about your art practice, which will be entirely subjective. You may find your truth and definitions, but they will be subjective. All good art has many meanings, many subjective accounts. But there is a dialectic between the objective and the subjective in art. The art object is a subjective object, and as such, it can be a source of knowledge that may be both subjective and objective. This dialectic is where art as research excels.

So you get into action and make art and agree with yourself that it is art using the 5 Assumptions, but central to this is the act of attending to what you make.

Attention

This is the central theme to work with art as research of personal experience.

The central theme here is that you make art and attend to what you make and what happens when you make it. This also assumes that, from an experiential point of view, what you attend to is your research. I want to thread a more theoretical story before I return to this as practice.

Art Making as Experience

In all art making, you intentionally make something happen as art. In making visual art, what you do makes an art object. This is your experience. But with making an art object, the object is the experience. With a figurative painting, a painting of something, this is not obvious. The intention is objective realism. But with the emergence of photography in the 19th century, the role of the painter in making images of things was surpassed. Painting changed. Painting became more about the experience of the painter, and thus, the audience. Intentions changed.

Here are two examples of visual ‘Art’ made by ‘Artists’ who exemplify this.

The first is an image of Jackson Pollock inhabiting the experience of making one of his drip paintings. Click on the image to get to an article about the making of these drip paintings and see more close-up images.

This serves as an example of how the painting may be understood as not just a painting, but the experience of the artist painting the painting. The artist’s subjective experience has been embodied, reified, made an object. It is an object. It is an objective subject. It is a subjective object.

In the article on the ArtWizard site, the author tells us ‘As the artist once said, he did not want to illustrate feelings, but to express them, spontaneously and immediately.’

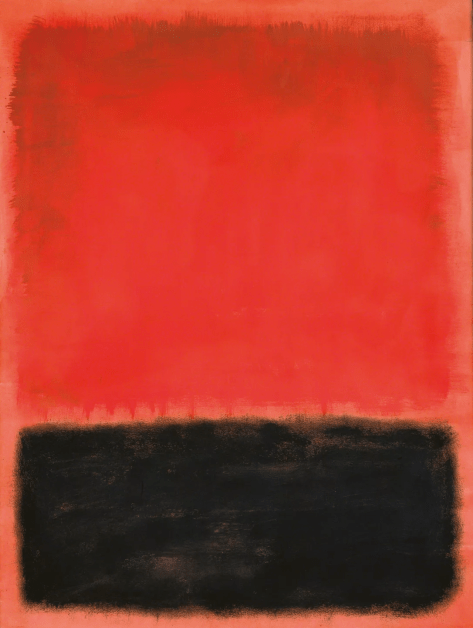

Next is by artist Mark Rothko.

In an article on Artsy website author Alexxa Gottardt quotes artist Mark Rothko, ‘ “Painting is not about an experience,” he told LIFE magazine in 1959. “It is an experience.” “The fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions,” he said in an interview in 1956. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”’

This art movement, Abstract Expressionism, emerged out of Surrealism in an attempt to make painting be about something rather than being an image of something. It surpassed Impressionism in the way it showed the artist’s subjective impression of a place rather than an objective image of a place. The paint is the point of the painting. In the 20th century, the importance of the individual and individual started became more important in the industrialised West.

The intentions of artists in the 20th century come closer to what we mean by art as research.

Art Making as Performance

But in this work proposed here, we are open to ideas about art without an object, like a painting or a sculpture. A novel, whilst an object to read, is about experience. The object, the book, is not the art. The art is in the reader’s experience of the words. The same goes for performance. The art is in the experience of being at the event, the opera, or the concert, or at the theatre. The experience is temporal and immediate. In performance, there is no lasting object made, but you still make something happen. We can use art making as a temporal, immediate experience to conduct art as research.

Influenced by working with experiential learning and Adventure Therapy, I trained to be a Drama and Movement Therapist in the late 90s using the Sesame approach. I emulated experiential approaches and went on to work therapeutically away from ‘Therapy’ in a clinical setting, and worked with experiential and dramatherapy approaches in the milieu. In many ways, this influenced the idea that we can’t all be artists, but we can all make art. Like all experiential approaches, I think it is intrinsically anti-institutional.

In this, I was always looking for sources that brought the arts into experiential paradigms. I had explored ways in which experiential paradigms could be found in the arts. In the visual or concrete arts, the art-making involves the creation of an object as experience or as an expression of experience. This subjective object offered an element to experiential approaches that could bring new ways of working with experiential learning. But in my own art making, with art as walking or working with the outdoors as art, we seek to leave nothing but footprints. The object was thus excluded. In all settings we can attend to experience, but with drama or performance paradigms, the attention to experience is the sole means of research.

From somewhere, I came across Performance Studies and the work of Professor Richard Schechner. His book Performance Studies – An Introduction proved to be full of intriguing and useful ideas.

There is much in the book, but the following are useful to understanding art as experiential learning, art as research and the role of intention and attention in such. These ideas are Restored Behaviour, As and Is Performance and Performativity.

Restored Behaviour is central to Performance Studies. It is a performance version of the cyclical plan-do-review experiential view. He puts performance as not just a thing of the stage but of everyday life. Of restored behaviour, Schechner says, ‘Performances of art, rituals, or ordinary life are “restored behaviours,” “twice-behaved behaviours,” performed actions that people train for and rehearse.’ Restored behaviour is behaviour in life and art that has been around the experiential learning cycle and is thus perpetually planned based on past experience. It describes the plan – do – review cycle, in art and life, as effectively, rehearsal.

By being able always to rework what you have done before, this presents us with an opportunity to make and remake who we are and what we do. Approaching art as experiential learning or experiential learning as art, as performance comprising restored behaviour, means we have scope to research who we may be what we may do. This directly connects the art and performance to experiential learning. Our intentions may include the availability for reworking our experience of the moment.

Is and As Performance reworks what art is and the intentional shifting of the boundary between art and life. Is Performance is what we encounter as theatre. This is a performance proper. As Performance is a way of encountering lived life off the stage as performance. We may take an experience and encounter, analyse, and research it as performance. Schechner offers different ways of understanding and enacting performance. He implicitly suggests we may do this intentionally.

Schechner asks of performance, “Where do performances take place?” A painting “takes place” in the physical object; a novel takes place in the words. But a performance takes place as action, interaction, and relation. In this regard, a painting or a novel can be performative or can be analysed “as” performance. Performance isn’t “in” anything, but between2.” He suggests that if we make art as experiential learning or as research, to make an object or not we can use our intention to analyse experience as performance. We may use ideas and practices in performance and performance studies as our mode of research of our experience.

Performativity as Schechner describes it, brings us closest to art as research. Schechner reminds us that performative is contested and open always to change of meaning. He says it is a key theme in Performance Studies. He cites many learned sources.

He finishes his chapter on performativity with Hamlet, the gravediggers (Hamlet, 5, 1: 11). Schechner tells us one gravedigger asserts, “An act hath three branches – it is to do, to act, to perform”. Schechner says ‘The Gravedigger divides an action into its physical attributes (“do”), its social aspects (“act”), and its theatrical qualities (“perform”). But why does he use the word “act” twice – first as an overall category and then as a subset of itself? Gravedigger is not so much repeating himself as he is proposing a situation where the smaller (“to act”) contains the larger (“an act”). He is also connecting “an act” as something accomplished in everyday life with “to act,” something played on the stage. The ultimate example of “to act” is “to perform” – to be reflexive about one’s acting.’

To be reflexive about one’s acting is, within the realm of performance studies, art as research, in which we are reflexive about our own experience. We act as if we are ourselves on stage, in performance, watching ourself as audience. If we intentionally approach our experience of art making as performance, or performative, our reflexivity, our attention to our attention, becomes a research tool of behaviour as it happens. If we make an object as art in the process, we create and retain an object that is our experience and may be approached retrospectively as a representation of behaviour. This broadens the scope of our research. We have objective evidence of a subjective experience that was intentionally open to us attending to our experience. It is in this act that the health benefits emerge. We have a way to research and change the way we experience ourselves doing things.

Richard Schechner, ever the performer, did a whole series of video shorts about Performance Studies with Restored Behaviour, Is and As Performance and Performativity which can be seen here.

Whilst performance may not produce a concrete object, the use of body and intention to do something rather than think about something, to enact ideas through practice, offers the researcher a much more material relationship with their research, their intention and their ideation, a kind of material thinking in which we attend to and act on concrete embodied experience.

Some Ideas about Material Thinking

Two interesting arts practitioners who have worked with theories and practices about material thinking, the capacity for arts materials and practices to act as a way of thinking through doing, are Barbara Bolt and Augusto Boal. Each uses different words to describe the experience, but the core phenomenon is similar.

In a great piece of writing by Bolt here she says, ‘Theorising out of practice, I would argue, involves a very different way of thinking than applying theory to practice. It offers a very specific way of understanding the world, one that is grounded in (to borrow Paul Carter’s term) “material thinking” rather than merely conceptual thinking. Material thinking offers us a way of considering the relations that take place within the very process or tissue of making. In this conception, the materials are not just passive objects to be used instrumentally by the artist, but rather the materials and processes of production have their own intelligence that come into play in interaction with the artist’s creative intelligence.’

In ‘Rainbow of Desire’, Boal writes in a different way about ‘Concretisation’ in the experience of artistic or therapeutic performance. He says, ‘Concretisation is the putting of ideas or thoughts into concrete form, concretisation being the act of materialisation of these desires’. He uses the word desire as an amalgam of idea and intention. He goes on to say ‘The desire becomes a thing. The verb becomes a palpable noun.’

Then of the artist/performer through the experience of doing, of acting, of action, he goes on to say, ‘In living the scene, she is trying to concretise a desire, in reliving it, she is reifying it. Her desire… transforms itself into an object which is observable, by herself and others. The desire, having become a thing, can be better be studied, analysed, and (who knows) transformed… Not only what one wants to reify is reified, but sometimes also things that are there but hidden.’ (pg 24 Rainbow of Desires).

Both Bolt and Boal advocate for material thinking. The materiality can be through a physical object, or through performance, an engagement with space. In both cases, we make some thing come into existence that previously did not exist. This was called poeisis by the greeks and included art objects and theatre. My proposal is that this is experiential at its core, and making art as an object or as a performance is a form of experiential learning. We make art and attend to what we make and what happens when we make it. So I did this and am telling you about what is happening now. This is what I made as an act of material thinking.

Return to Intention and Attention

And given that we are talking about intention and attention, we may describe the experience of making art, attending to what you make and what happens when you make it as research, or as meditation. Meditation may be taken as a form of research. We may approach art-making as meditation.

Meditation requires intention, attention and attitude here. We may choose and intend to meditate, we may attend to what we attend to, and we may do this work with an attitude of openness and detachment and non-judgement. This applies in daily experience, meditation, art making, art as research and all experience of all said. This triad is our research. This is our path to self-awareness and self care. We can do this with personal arts practice.

Shauna Shapiro, professor of psychology at Santa Clara University who works on mindfulness, talks about the triad of intention, attention and attitude as being the core components to mindfulness. Shapiro says ‘The awareness that arises out of intentionally paying attention in an open, kind and discerning way. This is all we are trying to do, it does not necessarily have to do with meditation practice…’ here.

What I am suggesting is that arts practice requires intention and attention. And making arts for health benefits from an attitude of openness to experience, of not judging oneself (as for example as ‘not an artist’) of being up for adventure and surprise and awe. Arts practice does not necessarily have to do with meditation practice’ but is intrinsically meditative, it both requires and develops intention, attention and attitude.

In the work of Pat B Allen mentioned above in Open Studio Process, Pat uses both meditative and artful process, the immediate experience of the art making, the breath and the image made. She says of the process ‘Returning to the breath and to pleasure are recommended if one gets “stuck.” We pay attention to ourselves and to each other, to the space and to the images, without desire, without expectation.

Of meditation, Allen quotes Shapiro as saying ‘In the context of mindfulness practice, paying attention involves observing the operations of one’s moment-to-moment, internal and external experience. This is what Husserl refers to as a “return to things themselves,” that is, suspending all the ways of interpreting experience and attending to experience itself, as it presents itself in the here and now. In this way, one learns to attend to the contents of consciousness, moment by moment. Attention has been suggested in the field of psychology as critical to the healing process.’

Art making is a return to things themselves, and in it we make a thing happen and may make thing that is our experience that we may see it materialised.

This can all get a bit exhausting. Art making inhabits the world of ‘Flow’, the being here now and forgetting yourself but fully being yourself. This is exhilarating but tiring. This is why you need periods of incubation in your art making. Inaction feeds action.

Incubation

Incubation is an established part of accounts of the creative process. It is essentially that thing when you are out with friends, and remember some piece of music but cannot remember it’s name. You go about your business, then suddenly, some time later, when you are no longer thinking about it, the name pops into your head. Some thing in your brain and body does some unbidden work behind the scenes and gives you the product of that work.

This phenomenon occurs in all settings. But in an art setting incubation is a deliberate or conscious forgetting, moving on from some art activity such that either unbidden or on return to such work, the work looks and feels different. On return you see things you did not see before. This can be both good and bad. Good if a new idea pops into your head and you do new interesting work. But it has a shadow expression when you think some idea you have is new, but when you look at old work, you see that you have been there already.

How you deal with this is interesting. It can be dispiriting, but applying the triad of meditation, if one works with intention to attend to attention, with an attitude of openness and detachment, this tells you something of what you attend to in the long term. It confirms continuity, it reminds you that your attention is variable. It teaches humility. It warns of procrastination.

In an arts and health context, I present two sources. One from arts practice and one from therapy. Both are fascinating and full of ideas for work.

Exposition

Exposition occupies the same place in the experiential learning cycle as ‘Review’, the looking back in order to look forward. In art as experiential learning, art as research, the maker is invited to intentionally attend to both what they make and what happens when they make it. Exposition has the suffix ‘ex-’ meaning ‘out of’ or ‘from’ as well as describing a past event or status, like an ex-husband.

It also has elements here of exposure or expose, “to leave without shelter or defence,” from Old French esposer, exposer “lay open, set forth, speak one’s mind, explain”.

It is also meant in an artistic sense as an alternative to exhibition. A public ‘Expo’ will have more of an element of explanation, like a World Fair. An exhibition will tend to have art on show with little explanation, but for the name of the artist and the name of the works.

Each person may find their own way of doing this, but the point is for it to bring together past and future actions, and true to the act of intentional attention, this always takes place in the present. So exposition may be seen to have the reflection upon attention of the maker to their present experience and the thing made as the product of action and record of the experience of action. The art is the experience.

The use of exposition in the place of review emerged out of material I was reading about art as research in post-graduate work in the arts and the arts therapies. This article, ‘The ‘Epistemic Object’ in the Creative Process of Doctoral Inquiry’ was very interesting and influential. It was part of a movement to bring the agent of the doctoral research to be art itself and not a written account of the art. The arts therapies have struggled to show the efficacy of the arts as a mode of treating illness. If one undertakes research, there is a need to show what you found. Exposition is a good way to describe this regard the arts.

In the article above, the authors talk about Peter Vergo’s description of ‘aesthetic’ exhibitions with ‘contextual’ exhibitions. ‘The former might have minimal additional information other than the artefacts themselves, and the process of understanding them is largely experiential and personal. In the latter, artefacts are complementary to some accompanying ‘informative, comparative and explicatory material’

Then they quote Michael Biggs ‘If the aim of research is to communicate knowledge or understanding, then reception cannot be an uncontrolled process. The interpretation of embodied knowledge presented in an uncontextualised way is an uncontrolled process.’

The article calls for an approach in which the process of making the art as research is exposed and explicated. The artefacts made as part of the research are shown, and the mode of making is experienced as an exposition. An exposition is part public show and part description of ideas and theories attached. Process and product is exposed to scrutiny.

The authors go on to talk about the artefact and ask, ‘If these artefacts are not ‘artworks’ – what are they?’ But the artform, the art object, and it’s making is subjective, open to interpretation. They refer to the art made and the art making as comprising epistemic things and call for a new epistemology of experimentation, in which research is treated as a process for producing epistemic things. Epistemic things are sources of knowledge but are also ambiguous, thus also the source of new knowledge. The authors say ‘For an epistemic object to have the potential to develop scientific research, it must embody a degree of uncertainty to be useful.’

In this, I see there is a tension between the explication of process and the inexplicability of the art made, the epistemic thing. The clear exposing of the process of making and the exposing the thing made, to interpretation, to new meanings and knowledge. Now, whilst this is aimed at the graduate show and the graduate thesis, as research practice, I think the same applies to personal arts practice as research of personal experience.

The authors say ’In the context of creative doctoral inquiry, the term ‘exposition’ seems very appropriate, as its suggestion of exposure and explication matches very well the key characteristics of good research – accessibility, transparency, transferability.’ Elsewhere it is called exegesis, the critical explanation or interpretation of a text, particularly obscure text with obscure provenance. Both would seem to work as a systematic and considered approach to an act of subjective consideration.

Exposition or exegesis, either way, the work done is subjective. It is a form of personal reflection and reportage. As a sequence, for ease of reference in writing, itself a sequence of words on a page, exposition leads back into ideation. It goes ‘Ideation. Intention. Preparation. Action. Attention. Incubation. Exposition. And back to Ideation. And the cycle starts again, happening, often, all at the same time. When devised, I liked the idea of all bits ending in -ion. I liked it aesthetically as a way to bring all the parts together. Then I actually looked up the meaning of the suffix -ion. What it said pleased me.

Art-making experience as the activity of -ions

The suffix “-ion” is a noun-forming suffix, often indicating an action, process, or state, derived from Latin. It’s commonly used to transform verbs into nouns, signifying the result or outcome of the verb’s action. I like that the whole thing moves nouns into verbs and verbs into nouns. Things in action. Actions named. Doing and describing doing are fused into a single entity. This so fitted what I was getting at.

Then I thought about ‘Ions’ as things I learned about in biology and chemistry, and physics. I went back to basics as taught at school and college. Ions are atoms which have gained or lost electrons. This makes atoms unstable and thus available to do something. Ions make something happen.

The atomist model of the material world goes back to the Greeks. It suggests all the massive variety of big things we experience are made of a smaller set of smaller things called ‘atoms’. We take it for granted now. It is a god-damned scientific fact that we are made of atoms.

And atoms are made of electrons orbiting a nucleus, and all are sub-atomic particles, making the material world. We must go to philosophy or metaphysics to discuss whether some thing exists beyond matter. We have fields and energy and matter, and matter may change into energy and back, in the sun or in an atomic bomb.

It is all physics, if you believe in physics, but in biology, which I studied, ‘ions’ are central to making biological stuff happen, and I am that biological stuff in action.

I am sure a purely objective materialistic account of ions would not fit what I am about to suggest. But I liked the idea that ions are an unstable form of the stability of the atom. Ions are highly reactive with other ions. I like the idea that these seven elements are unstable, reactive, interactive forms that interrupt the stability of the atomistic stable material world, that react together to do something. Ions are things that make other things happen. Like art making, ions exist in process and in relation to other ions to change matter to make something happen.

I want to leave with the idea of art making as a disruption of a stable state of the material world. It is, like ions, made of stable material, but nudged briefly into an unstable state. This is my imaginal exposition of art making as a disruption of a stable world, that interacts with itself to make something happen.