My visit to the Solway was prompted by a need for a large space without physical barriers to explore what would happen if I walked a drawing of an model of experiential learning through the arts. In doing so my idea about my model changed.

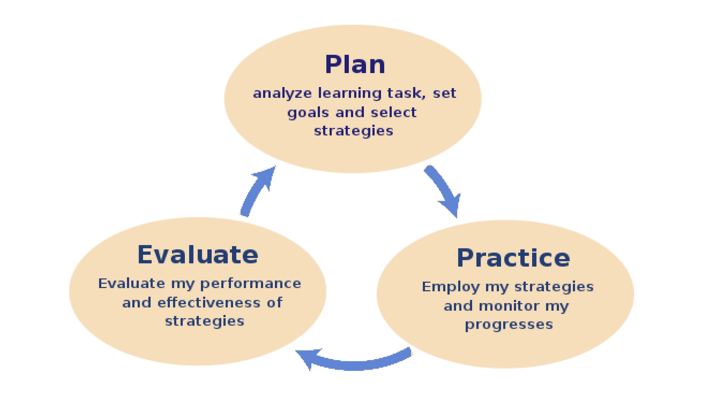

The original model

Models are slippery things. Their appeal is that they appear to give a fixed image of a thing, but in practice whilst they serve as a very useful signpost about which way to go when you set off, the thing you find when you get there is never fixed. So the walk was undertaken as an experiment ‘to explore what would happen…’

What the model predicted was that a number of factors would contribute to the art making. In this case my thoughts were that source material would be Richard Long and the walking and land artists. My personal arts practice or art made included using a GPS and walking to make a mark on the landscape and experience of film making as a means of exploration, reflection and expression of experience. I drew on ongoing research and theory about the outdoors as a liminal space and art making as adventure, as a journey of uncertain outcome, and Shaun McNiff’s ideas about witnessing in the arts therapies1.

The model was correct in that my path would lead in to and out of the art making on the day and on to more art making, research, source materials and theory, and that the generic coloured blobs would be specific to the art making experience. My initial thinking after the event went to ideas about performance and the epistemic object and further trips to photograph and film, reporting this through blog posts.

At the centre of this, an act of art making and poiesis occurs. Something comes into existence that did not exist before and it is called art. It is art by convention, because all this could describe the making of a cup of tea. To this conundrum ’Why is this art?’ one asks the question asked by artist John Baldessari, “Why is this not art.” It is art because it was my intention to make art and my act was guided by research, reference to existent artform and artists, theories of art and my experience of art I made before.

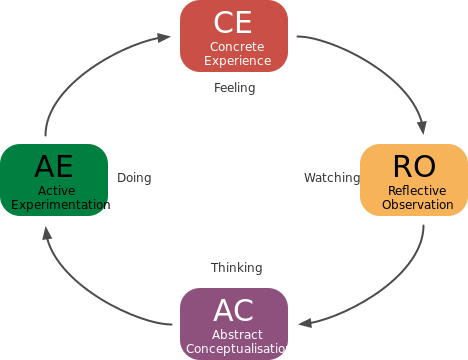

But there was something incomplete about the central concentric circle structure. I was interested in the model showing how each experience of art making occured within a loop of experience, like in Kolb’s learning cycle.

But like the Kolb model is an ideal form which would be expressed differently depending on the setting, the strict concentric form may vary depending on the setting. My experience of art-making was, however, that in making art I stepped away from the day to day life experience and went to a different place. This could state is sometimes known as a ‘Flow’ state from work by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. You get in the zone of concentration and attention, of doing and the senses. But for art-making as experiential learning or personal research or art therapy, you enter a state that is similar to a meditative state, like flow with awareness. You are focussed on making art but also on what it is that you have made and what happens when you make it.

So in the model, as well as cycling through an iterative learning process, there was a linear path away from the world, into a creative state where something happens in partnership with your artform, then back to the world.

Reflecting on how the model changed

On return home from the Solway and recollecting the emergence of performance I went back to my Dramatherapy training. In a dramatherapy session you work with a basic three part structure. ‘It begins with a physical warm-up leading to the Main Event, the place where the real action is. It concludes with the ‘grounding’, returning people from the ‘Land of Imagination’ to their own everyday selves.2’

During the walk recreating the drawing, the shift from walking to dancing, from recreating the drawing to improvising and performance emerged unbidden. One could say this idea came out of my imagination or my unconscious, or it was the product of a state of flow, or having danced in the past, I simply remembered something from my past related to what I was doing in the present.

So there are two things here. One is a linear journey into a place with some degree of separation from the everyday world, into ‘flow’ or ‘Land of Imagination’, followed by a return. This is a linear journey in an iterative looping cycle of learning. The other is the experience of being in ‘flow’ or the ‘Land of Imagination’. This is an experience of art making as somewhat separated from ones day to day life.

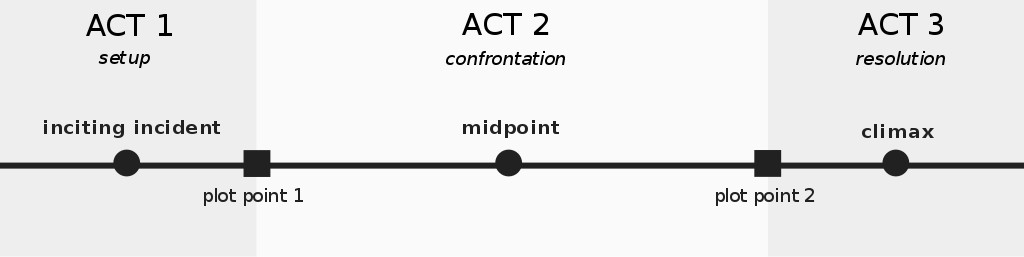

Something like this three-stage process occurs in many settings. In story and in film and theatre there is a thing called the ‘Three Act Structure.’ On one hand, this is as simple as a beginning a middle and an end or it is sometimes understood as set-up, confrontation and resolution. Many interpretations exist and there are examples to be found of its use in say cinema, but it is not without some contention. Like one article says ‘The true three-act structure isn’t a formula, it keeps your beginning separate from your middle and your middle separate from your end. That’s it.’

But the ‘beginning, middle and end’ could be seen as a universal or archetypal structure. For example at Outward Bound, in experiential learning, you worked with a ‘training, main and final expedition’. Your training expedition was where you taught skills, the main expedition was where you had the conflict as you got the people to move from being a group to being a team. Final was the unaccompanied independent journey.

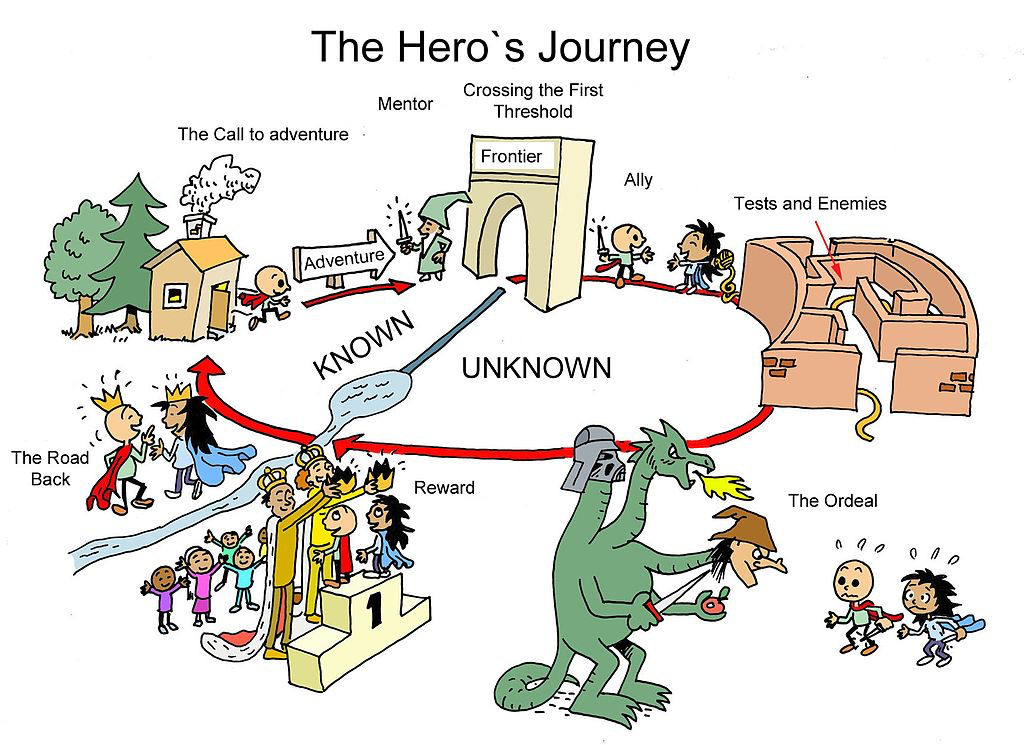

In care, we worked with a conflict model and resolution tool called ‘ABC Charts’ meaning A – antecedent, B – behaviour, and C – consequences. Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey has a specific expression and detail but is also a three-stage form, the call to adventure, the test and the return.

But the simple, warm up, main event and grounding of dramatherapy mentioned above can be also seen in a form described by Victor Turner and Arnold van Gennep as Rites of Passage.

Turners Initiation Model

From Schechner3

The above diagram is from Victor Turner a British anthropologist who theorised the above from studies of non-western settings at the top, and western settings at the bottom. This is a three stage journey of return that is linear and cyclical and has a central liminal or liminoid space somewhat separated from everyday life called The Land of Imagination in the dramatherapy model.

Art as liminal space

My proposal is that art making and experiential learning could be understood as having some some elements of the above structure in their practice. I don’t think it is coincidental that after a while on the Solway Walk, I spontaneously rediscovered that I could do the walk as performance. This could be seen as me, albeit briefly, entering a mild ludic state.

There is a lot to this seemingly simple experience of walking in circles on a beach like an idiot. Not least the idiocy. I was being playful throughout. I was in the land of the Trickster or the Court Jester, at once playful and challenging, the one who can perform recombination and inversion.

This is also adventure. The journey between departure and arrival. The journey of uncertain outcome with misadventure available. The three part expedition cycle of Outward Bound. On a slave ship, the middle passage. The refugee in the hands of the trafficker. It is not a thing of the past.

To me there is also something in this of being in the Solway, a liminal space if ever I saw one, between two countries, high and low water, land and sea. To me this is also a state of walking. In walking you are between places, outdoors, in a state of flow, and returned to a mode of existence that predates all of the modern world.

So after a few weeks of reflection my research led me a realisation. The experience was ‘like’ a lot of things, from experiential learning, theatre, anthropology, adventure sports, performance art, and conflict resolution, to Outward Bound and Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey.

This could also be applied to many arts based contexts and the model has ART FORM as a liminal or liminoid experience at it’s heart, the same as dramatherapy. But the artform that fits this experience best if what is known as Walking Art.

My exploration of my Solway walk has reached a convenient place to move on and in my next set of posts I want to look at Walking Art with a particular focus on it’s scope for promoting health and wellbeing.